|

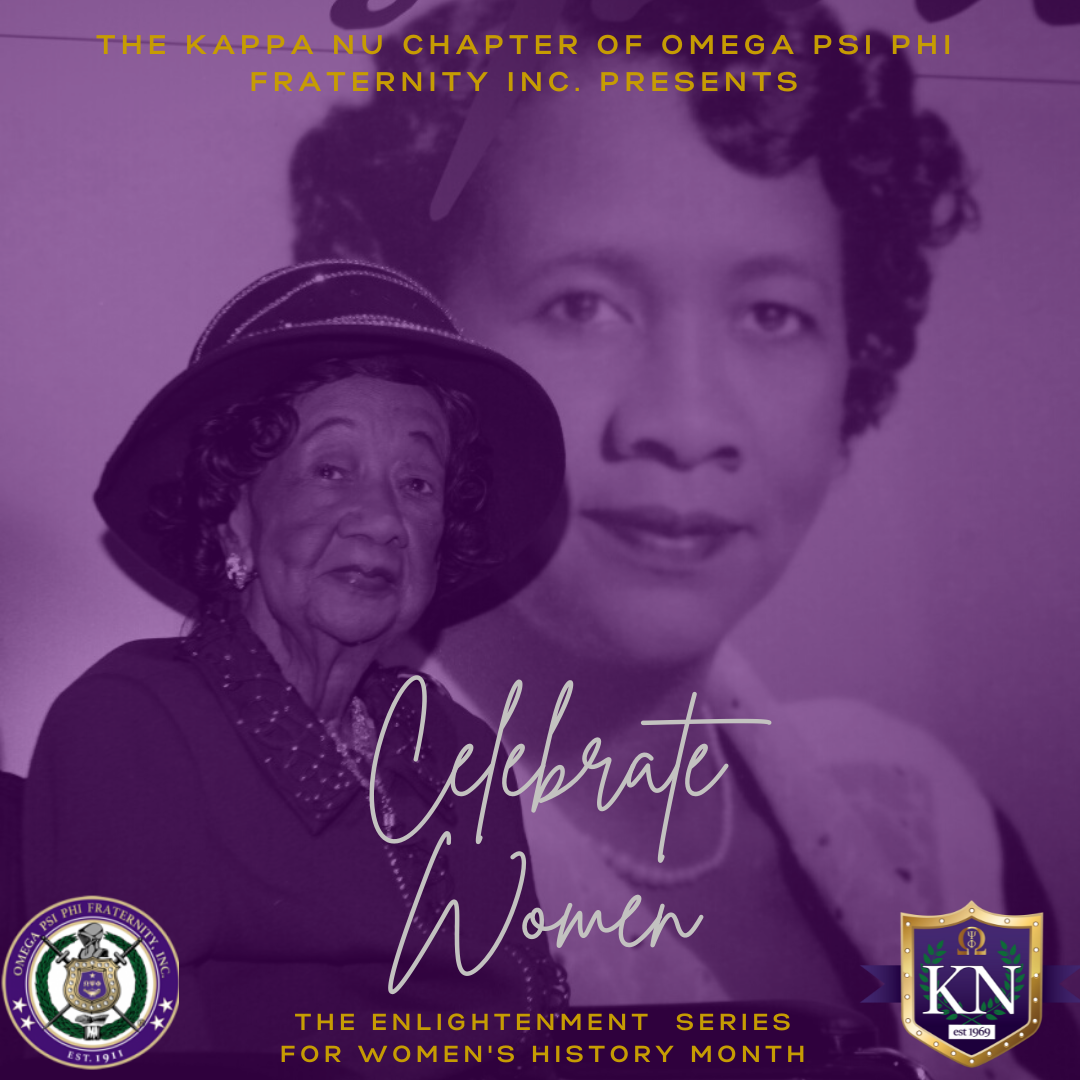

The Godmother of Civil Rights Dorothy Height Did you know that civil rights trailblazer Dorothy Height was a past President of Delta Sigma Theta? Dorothy Height served as the National President of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc from 1946-1957. Dorothy Height (March 24, 1912–April 20, 2010) was a teacher, social service worker, and the four-decade-long president of the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW). She was called the "godmother of the women's movement" for her work for women's rights and was one of few women present on the speaking platform during the 1963 March on Washington. Early Life Dorothy Irene Height was born on March 24, 1912, in Richmond, Virginia, the eldest of two children of James Edward Height, a building contractor, and nurse Fannie Burroughs Height. Both her parents had been widowed twice before, and both had children from earlier marriages who lived with their family. Her one full sister was Anthanette Height Aldridge (1916–2011). The family moved to Pennsylvania, where Dorothy attended integrated schools. In high school, Height was noted for her speaking skills. She even earned a college scholarship after winning a national oratory competition. She also, while in high school, began participating in anti-lynching activism. She was accepted at Barnard College but was then rejected, with the school indicating it had filled its quota for Black students. She attended New York University instead. Her bachelor's degree in 1930 was in education, and her master's in 1932 was in educational psychology. Beginning a Career After college, Dorothy Height worked as a teacher in the Brownsville Community Center in Brooklyn, New York. She was active in the United Christian Youth Movement after its founding in 1935. In 1938, Dorothy Height was one of 10 young people selected to help First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt plan a World Youth Conference. Through Roosevelt, she met Mary McLeod Bethune and became involved in the National Council of Negro Women. Also, in 1938, Dorothy Height was hired by the Harlem YWCA. She worked for better working conditions for Black domestic workers, leading to her election to YWCA national leadership. In her professional service with the YWCA, she was assistant director of the Emma Ransom House in Harlem and was later executive director of the Phillis Wheatley House in Washington, D.C. Dorothy Height became national president of Delta Sigma Theta in 1947, after serving for three years as vice president. National Congress of Negro Women In 1957, Dorothy Height's term as president of Delta Sigma Theta expired. She was then selected as the president of the National Congress of Negro Women, an organization of organizations. Always as a volunteer, she led NCNW through the civil rights years and into self-help assistance programs in the 1970s and 1980s. She built up the organization's credibility and fund-raising capacity such that it was able to attract large grants and therefore undertake major projects. She also helped establish a national headquarters building for NCNW. She was also able to influence the YWCA to be involved in civil rights beginning in the 1960s and worked within the YWCA to desegregate all levels of the organization. Height was one of the few women to participate at the highest levels of the civil rights movement, with such others as A. Philip Randolph, Martin Luther King, jr., and Whitney Young. At the 1963 March on Washington, she was on the platform when King delivered his "I Have a Dream" speech. Legacy Dorothy Height traveled extensively in her various positions, including India, where she taught in Haiti and England for several months. She served on many commissions and boards connected with women's and civil rights. She once said: "We are not a problem people; we are a people with problems. We have historic strengths; we have survived because of family." In 1986, Dorothy Height became convinced that negative images of Black family life were a significant problem. She founded the annual Black Family Reunion, an annual national festival, as a result. In 1994, President Bill Clinton presented Height with the Medal of Freedom. When Height retired from the presidency of the NCNW, she remained chair and president emerita. She wrote her memoirs, "Open the Freedom Gates," in 2003. Over her lifetime, Height was given many awards, including three dozen honorary doctorates. In 2004, 75 years after rescinding its acceptance, Barnard College awarded her a B.A. Please read up on other important women in our history by visiting www.kappanuques.com

This story appeared originally in the 19th News, at: https://19thnews.org/2020/08/black-sororities-in-suffrage/ ‘A history of great glory’: The consequential, evolving role of Black sororities in suffrage From suffrage to 2020’s vice presidential nominee, Black sororities have been part of the political process. But some sisters believe their actions could be bolder. Author: Ko Bragg, General Assignment Reporter August 20, 2020, 10:49 a.m. ET On March 3, 1913, the day before President Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration, nine White women dressed in brilliant white rode down Washington, D.C.’s Pennsylvania Avenue in an official state car, representing the only states that had given women of their race the right to vote. More than three dozen White women dressed in black flanked the vehicle on foot to demonstrate how much of the nation was home to vote-less women. “No Country Can Exist Half Slave and Half Free,” the banner above them read. The irony in 1913 was overwhelming. The White women who organized the Woman Suffrage Procession, which attracted thousands to protest for the right to vote, advocated for a supremacist symbol of their priorities; Black women could march — but they had to bring up the rear. Among the Black women who showed up to the parade were 22 college women from Howard University. As liberal arts students at the historically Black school in the nation’s capital, they had front row seats to the suffrage movement — and they wanted their fair share of liberation. Their college, led by a male dean noted for being unsympathetic to women’s suffrage, did not want the women to attend the march; the talk in Washington was that it was gearing up to be a contentious, and potentially dangerous, demonstration. The college eventually acquiesced and allowed the group to attend — under the terms that a man accompany them as a chaperone. The women were excited. It would be their first public demonstration, and this particular group had recent practice advocating for themselves and their values. In the months leading up to the march, they rebelled from the nation’s first sorority for Black women, Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc., finding it to be more of an extension of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc., even if just in name only, and not designed to respond to the societal issues of their time — the Great Migration, the aftermath of World War I, a thriving suffrage movement. These women needed something more than a social club. In January 1913, two months before the women’s march, the group of 22 finalized their incorporated status and renamed themselves: Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc. — delta, like the Greek letter used to denote change in mathematics — underscoring their motivations. As the Deltas made their way to Pennsylvania Avenue, a quarter-million spectators greeted them. Bertha Campbell, valedictorian and only Black student at her Colorado high school, said the men threw things at them and yelled. “They were saying ‘Go back to the kitchen,’ There were a lot of police and you didn’t dare step onto the sidewalk,” Campbell is quoted saying in historian Paula Giddings’ “In Search of Sisterhood,” a chronicle of the first 75 years of Delta Sigma Theta. Florence Toms, a Washington, D.C., native with an affinity for elephants (which became the sorority’s unofficial symbol), said her family told her not to march. She defied their wishes — as the tallest of the group, she was in charge of holding the banner. With Toms, anxious but exhilarated, the Deltas joined the thousands of women demanding their voices be heard at the polls. “It’s been very good to reexamine suffrage … to sort of understand what happened, and, of course, the resilience of Black women just to be determined to get their rights all the way through — it’s a history of great glory,” Giddings told The 19th in an interview. Giddings, who also authored the biography “Ida: A Sword Among Lions,” says that despite myths that all other Black women marched behind the White ones, Ida B. Wells — journalist, suffragist, founder of the first Black women’s suffrage club, future member of Delta Sigma Theta and civil rights leader — famously marched with the White women of Chicago. Giddings said the group of Deltas that marched that day in D.C. rejected the racist relegation to the rear of the resistance, too. “In that parade, the refusal to march in a segregated section was really so important,” Giddings said. “If Black women had complied with those orders to march in the back, women’s suffrage would be forever associated with white supremacy. ” The historic moment of what was the first suffragist march in Washington was not lost on the students: Madree White, the first woman staffer at the Howard University Journal, wrote that the women’s refusal signaled to the city, the nation and the world that Deltas took a stand. Toms expected criticism, but knew the importance of them showing a united front. “Those were the days when women were seen and not heard,” Toms said later of the moment. “However we marched that day in order that women might come into their own, because we believed that women not only needed an education, but they needed a broader horizon in which they may use that education. And the right to vote would give them that privilege.” The suffrage march was just the beginning. The Deltas’ decision to participate was not made lightly — it was made despite heightened risk to their lives. This act of sisterhood and solidarity, laid the foundation of an institution that would endure for over a century, inducting some of the most powerful, change-making, well-known Black women throughout history, including Ida B. Wells, Marian Wright Edelman, Shirley Chisholm, Mary Church Terrell, Mary McLeod Bethune, Loretta Lynch, Cicely Tyson, Angela Bassett, Nikki Giovanni, Soledad O’Brien, Melissa Harris Perry and younger members still building their brand, like the author of this piece. “It was emblematic of their desire to be really involved with service and civics and public issues, which sororities weren’t necessarily [involved in] so much before,” Giddings said. “So this was very kind of intentional for this to be their first act.” In the 107 years since then, Deltas fought for suffrage and equality as Black women who would not fully gain the right to vote until 1965, and still face significant roadblocks. Like all “purposive institutions,” as Giddings called the sorority, Delta has had to find its footing as times progressed — through the Black Power years, the Civil Rights Movement and, now, the Black Lives Matter movement — while leaving room to embrace members of all political persuasions. Delta, Alpha Kappa Alpha, Zeta Phi Beta Sorority, Inc., and Sigma Gamma Rho Sorority, Inc. are the four Black sororities in the National Pan-Hellenic Council, a nine-member collaborative for Black Greek-letter organization that’s often referred to as the Divine Nine. Each organization has become service-oriented, with less of a social focus than White fraternal organizations. And each advocated for betterment in the Black community throughout history. It is certain that not all inductees agree with leadership’s trajectory, and this is also true of the quarter-million members of Divine Nine sororities. As the nation grapples with many questions of race and gender in the wake of a national reckoning on race and the centennial of the 19th Amendment, some want their sororities to take a more front-row approach. “There’s a certain kind of unity that is difficult to sustain if you have a highly controversial political agenda,” Giddings said. “But it is also a reason why these organizations still exist, and will be growing, and will be around for a long time.” In the spring of 2018, Eva Dickerson became a Delta at Spelman College, a historically Black college for women founded in 1881. Thinking back about herself as a first-year student, seeing the Deltas on campus in their leadership roles in this “world of blackness,” Dickerson, now 23, couldn’t find the words to describe what she felt at first. “Grounding,” she finally decided. Dickerson joined the ranks of her role models when she won the prestigious Miss Spelman pageant shortly before she became a member of the sorority. However, as she got deeper into Delta, it registered that she did not always align with her sisters or the organization itself. The “starry-eyed, puppy love” she felt for Delta transitioned into an understanding that some images appear differently in the rearview. “You get to the other side and you learn more about Delta, which is that Delta is not a monolithic organization,” she said. “It is made up of hundreds of thousands of diverse varied women and you have different experiences with each of them.” Through the years, some members feel Delta has strayed from its roots as an organization founded in protest. In 2014, Delta issued an urgent demand for members not to display paraphernalia with the sorority’s name at protests stemming from the killing of Mike Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. Alpha Kappa Alpha asked the same of its members. Dickerson wondered what precedent that would set for the little girls. “Ferguson didn’t just blow up because Mike Brown was murdered,” Dickerson said. “Ferguson blew up because of the extreme disenfranchisement, the segregation, the police terror. This is decades and decades, and Delta, you’re going to tell your members they can’t represent you at a protest? The sorority that was founded by protest? Oh.” Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc. nor Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc. responded to The 19th’s request for comment. However, during this resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement amid the pandemic and following the police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, among others, all of the Divine Nine, as well as other Black women’s groups, signed a letter✎ EditSign condemning violence against “Black women, Black men, Black girls, and Black boys by police and vigilantes.” Alpha Kappa Alpha provided a scholarship for Floyd’s daughters and granddaughters to attend any HBCU of their choice. This was not the first time Delta Sigma Theta would have to reenvision itself to keep up with the times. As Giddings wrote of her sorority in “In Search of Sisterhood,” Delta’s role to transform the individual was clear, but its other roles were not always so defined. “The role of the sorority itself in Black political life has been less clear — and in highly charged times of Black militancy, such as the sixties, it has often been thrown into a crisis of identity and relevance as a primarily social organization,” she wrote in her book. During the Civil Rights Movement, the overwhelming political pressures and climate forced the sorority into more direct action. In the 1960s, Delta created a Student Emergency Fund, as more than a thousand chapters nationwide raised money to pay fines and bonds for those arrested during sit-ins and other demonstrations. In Arkansas, Daisy Bates, the president of the NAACP chapter in Little Rock, Arkansas, was being terrorized for trying to integrate the schools. In the wake of her home being bombed, there was a growing consensus among younger members of Delta who wanted to be more hands-on in such issues, and Little Rock became the stage. The sorority organized fundraisers for the Little Rock Nine and Bates, providing money and direct aid as well. Eighty-three chapters of the sorority bought ad space to keep Bates’ paper, the Arkansas State Press, afloat. Bates became an honorary member of the sorority. The sorority also raised money for a Mississippi teenager named Brenda Travis, who was arrested when she sat in a White-only area of a bus terminal as she participated in the Freedom Rides. The sorority gave more than $3,600 in aid for Travis and the 70 high school students who protested and were expelled for supporting her. These are among the kinds of actions that inspired Dickerson as she learned about the history of the organization, and now serve as the catalyst for why she wants it to return to this style of engagement. Dickerson says that criticizing Black organizations, particularly legacy organizations, is difficult: They’re already dealing with their own struggles, be it financial or social. However, Dickerson believes in a constructive, if sometimes critical, dialogue out of a love for her city, her sorority, her college. “But some people can’t hold that the critique is the love, and they only feel the sharpness,” she said. Although members of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc. did not attend the suffrage march as an organization, some of its most notable members have long fought for voting rights access and civil rights for more than a century. It counts Anna Julia Cooper, Coretta Scott King and her daughter Bernice King, Mae Jemison, Maya Angelou, and Rosa Parks among its members. Despite criticisms from the founders of Delta Sigma Theta, Alpha Kappa Alpha, the nation’s first sorority for Black women, has throughout history followed its mission, to be “in service of all mankind,” by supporting teachers and the hungry in the Mississippi Delta, funding job trainings for Black people and lobbying against lynching. In these times, its most talked about member might be Sen. Kamala Harris, the first non-White woman to be on a major-party ticket. Adorned in pearls, a symbol of her sorority, Harris accepted the Democratic nomination for vice president last night during the Democratic National Convention. She enumerated all the people she considered to be her family, the one you’re born into, and the one you choose. “Family is my beloved Alpha Kappa Alpha, our Divine Nine, and my HBCU brothers and sisters,” she said.

The Legend of Stagecoach Mary Also known as Mary Fields, Stagecoach Mary was one of the toughest ladies of the Old West. Born as a slave on a Tennessee plantation in 1832, she gained her freedom after the Civil War and the resulting abolition of slavery. After the Civil War Mary made her way west where she eventually settled in Cascade County, Montana. In Montana Mary would gain a reputation as one of the toughest characters in the territory. Unlike most women of the Victorian Era, Mary had a penchant for whiskey, cheap cigars, and brawling. It was not uncommon for men to harass her because of her race or her gender. Those who earned her disfavor did so at their own risk, as the six-foot-tall two hundred pound woman served up a mean knuckle sandwich. According to her obituary in Great Falls Examiner, “she broke more noses than any other woman in Central Montana”. In Montana Mary made a living doing heavy labor for a Roman Catholic convent. She did work such as carpentry, chopping wood, and stonework. However, it was her job of transporting supplies to the convent by wagon that would earn her the name “Stagecoach Mary”. The job was certainly dangerous, as she braved fierce weather, bandits, robbers, and wild animals. In one instance her wagon was attacked by wolves, causing the horses to panic and overturn the wagon. Throughout the night Stagecoach Mary fought off several wolf attacks with a rifle, a ten gauge shotgun, and a pair of revolvers. Mary’s job with the convent ended when another hired hand complained it was not fair that she made more money than him to the townspeople and the local bishop. When the bishop dismissed his claims, he went to a local saloon, saying that it was not fair that he should have to work with a black woman (he said something much more obscene). In response, Mary shot him in the bum. The bishop fired Mary, and she was out of a job. After a failed attempt at running a restaurant, Stagecoach Mary was hired to run freight for the US Postal Service. Today she holds the distinction of being the first African American postal employee. Despite delivering parcels to some of the most remote and rugged areas of Montana, Mary gained a reputation for always delivering on time regardless of the weather or terrain. At the age of seventy, Stagecoach Mary retired from the parcel business and opened a laundry. In one incident when a customer refused to pay, the 72-year-old woman knocked out one of his teeth. For the remainder of her life, Mary settled down to peace and quiet, drinking whiskey and smoking cheap cigars. She passed away in 1914 at the age of 82. |